In 1972, a plane carrying a Uruguayan rugby team crashed deep in the Andes Mountains, leaving survivors stranded in one of the world’s most unforgiving environments. With no way to call for help and little hope of rescue, they faced extreme cold, hunger, and isolation. Over the next 72 days, their endurance was tested in unimaginable ways, forcing them to make unthinkable decisions. This is not just a story of survival—it’s a testament to human resilience in the face of overwhelming odds.

Flight 571’s Descent into Nightmare

On October 13, 1972, a chartered plane carrying 45 people, including Uruguay’s Old Christians rugby team, crashed into the remote Andes Mountains during bad weather.

Stranded at 12,000 feet in brutal cold, survivors faced starvation, injuries, and no contact with rescuers. Search efforts were called off after eight days with no results.

After 72 days, only 16 survived. They endured avalanches and hunger, ultimately resorting to cannibalism—a haunting but necessary decision that turned tragedy into an extraordinary tale of human endurance.

It All Began With a Rugby Tournament

Uruguayan Air Force Flight 571 carried 45 people: five crew members, 19 members of the Old Christians Club rugby team, and their friends and family.

The team, made up of students and alumni from Stella Maris College in Montevideo, was headed to Chile for a friendly match against Santiago’s Old Boys Club.

What began as an exciting sports trip quickly turned catastrophic. Among those on board were doctors, students, and relatives—all unaware of the ordeal they were about to face.

An Ominous Delay in Mendoza

On October 12, 1972—the day before the crash—bad weather forced Flight 571 to land in Mendoza, Argentina, halting their journey just before crossing the Andes.

It felt like a minor inconvenience. But in hindsight, it was a quiet warning. The mountains were restless, and the worst was still to come.

However, after consulting a pilot who had just flown in from Chile and reported acceptable conditions, the crew called passengers to board at 1:00 p.m. The plane departed at 2:18.

A Fatal Miscalculation in the Clouds

The aircraft was a Fairchild FH-227D, just four years old, piloted by experienced pilots Colonel Julio César Ferradas and co-pilot Lieutenant Colonel Dante Héctor Lagurara.

Flight 571’s route was clear: cross the Andes at 6,000 meters, fly over the Chilean town of Curicó, then turn north toward Santiago. That never happened.

At 3:08 p.m. on October 13, the plane turned to enter the mountains. By 3:21, co-pilot Lagurara radioed Chilean control, claiming they had reached the Planchón Pass.

By The Time They Realized Their Error, It Was Too Late

Believing they had cleared the Andes, co-pilot Lagurara contacted Chilean air traffic control again, claiming they could see Curicó and requesting to turn north.

Permission was granted. Assuming they were safely past the mountains, the pilots began descending to 3,500 meters—well below what was safe for that region.

But they were wrong. The peaks hadn’t been left behind—they were still deep inside the Andes. By the time they realized the error, it was already too late.

Trapped by Thin Air: How Reduced Speed Sealed Their Fate

The pilots soon realized their mistake—they were still deep within the Andes, not beyond them as they had believed just moments earlier.

Desperately, they reduced speed and tried to ascend, but the aircraft entered a snow pocket that caused it to lose even more altitude.

Then came the inevitable: the Fairchild’s right wing struck a mountainside. The plane shattered on impact, marking the start of an unimaginable fight for survival.

From Laughter to Panic in Seconds

When the crew told passengers to fasten their seatbelts, many laughed. The first bumps felt like ordinary turbulence—nothing the team hadn’t flown through before.

But the shaking worsened. The mountains looked alarmingly close, and the mood shifted instantly. Fear replaced laughter as passengers realized something was terribly wrong.

They heard the engines roaring at full power, but it made no difference. The plane wasn’t climbing—just trembling, straining, and inching closer to disaster with every second.

The Crash Unfolded a Storm of Metal and Terror

The first explosion came as the right wing slammed into a mountain, snapping off and tearing away the tail, instantly ejecting crew and passengers into the air.

Moments later, the left wing broke off too—ripping through the fuselage before falling away. The aircraft, now barely a shell, spiraled toward destruction.

Screams echoed inside the shattered cabin. Horror filled the space where calm had been minutes before. What remained of the plane was heading straight for the ground.

Seconds of Chaos: The Final Impacts and More Lives Lost

After the first collision, the aircraft surged forward and upward for about 200 meters (660 feet) before the left wing struck a rocky outcrop at 14,400 feet.

The impact tore the wing off, and one of its spinning propellers punctured the fuselage. Two passengers—Daniel Shaw and Carlos Valeta—were ejected through the rear opening.

The front section flew through the air, then slid 725 meters down a steep slope at 350 km/h before crashing into a snowbank, instantly killing the pilot and others onboard.

The Wreckage Came to Rest in the Valley of Tears

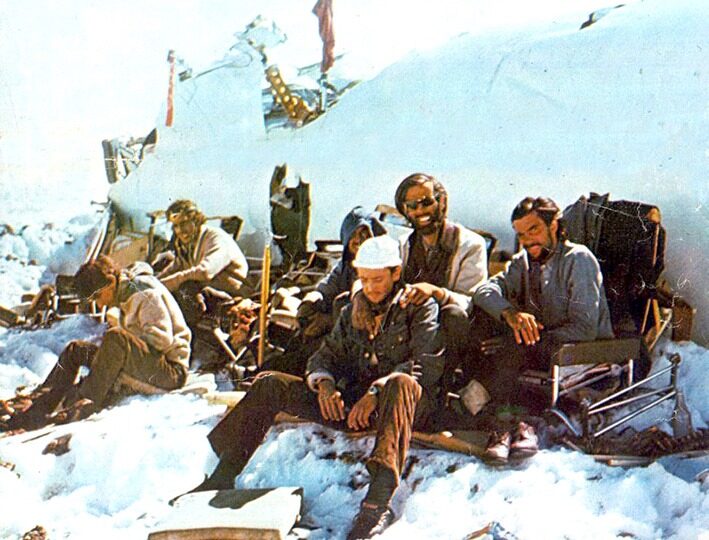

At 3:34 p.m., the shattered fuselage finally came to a stop after sliding through the snow and slamming into the base of a mountain slope.

The crash site was located at 11,712 feet above sea level, between Chile’s Tinguiririca volcano and Argentina’s Cerro Sosneado—isolated, freezing, and far from any help.

This desolate stretch of the Andes would later be named the Valley of Tears. It’s where the survivors endured 72 unimaginable days in the heart of the mountains.

The First Night: Death in the Snow

In total, the crash killed three crew members instantly, and ten passengers—some ejected from the plane, others crushed by the impact.

That night, four more people died from severe injuries and the freezing cold, including team members Francisco Abal, Gastón Costemalle, and friends Guido Magri and Marcelo Pérez.

By morning, 17 lives had already been lost. The remaining passengers awoke to a shattered world of snow, silence, and the overwhelming weight of what had happened.

Thirty-Three Survivors, Countless Injuries

Thirty-three passengers survived the crash, though many were seriously injured. The force of impact had ripped seats from the floor, crushing bodies against the cockpit wall.

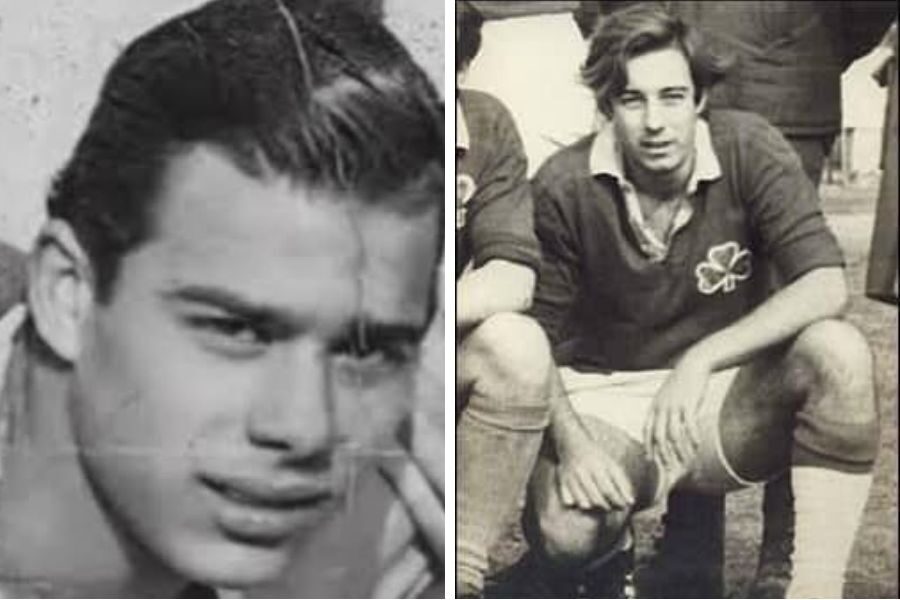

Roberto Canessa and Gustavo Zerbino, both second-year medical students, quickly assessed injuries, performing triage to identify who needed help most urgently amid the chaos.

Nando Parrado suffered a skull fracture and fell into a coma for three days. Others, like Enrique Platero and Arturo Nogueira, endured gruesome wounds but still helped however they could.

When The Flight Didn’t Arrive in Chile, a Search Began

When Flight 571 failed to arrive in Santiago on schedule, Chile’s Air Search and Rescue Service (SARS) was alerted that the aircraft was missing.

That same afternoon, four planes were dispatched to search the estimated crash zone, scouring the Andes until darkness forced them to return without success.

By 6:00 p.m., news of the missing flight reached Uruguayan media. What had begun as a routine trip now captured national attention, and growing concern for those on board.

A Hidden Crash and a Growing Search Effort

Chilean rescue officials, analyzing radio signals, concluded the plane had gone down in one of the most remote and inaccessible regions of the Andes.

They called in the Chilean Andean Relief Corps (CSA), unaware that the crash site was just 1 km east of the Argentina-Chile border and 21 km from Hotel Termas.

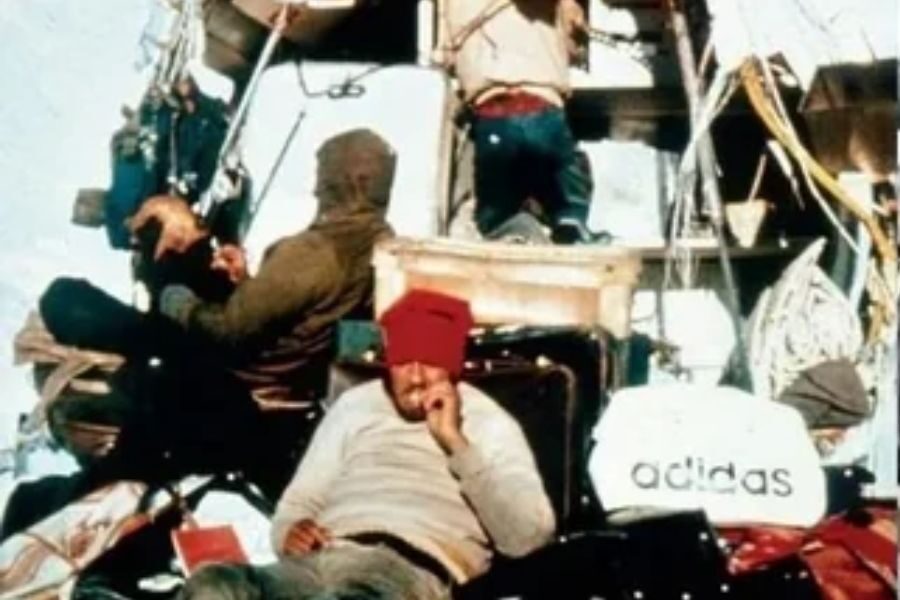

On the second day, eleven planes from Argentina, Chile, and Uruguay searched the area. Some flew directly over the survivors—but missed the white fuselage camouflaged by snow.

Their SOS Failed Signal, and the Search Was Abandoned After Eight Days

Hoping to signal planes, survivors tried writing “SOS” on the fuselage with lipstick, but ran out before the letters were large enough to be seen from above.

Despite daily flyovers, rescuers saw nothing. The terrain was harsh, the weather unforgiving, and optimism faded with each fruitless hour spent scanning the mountains.

On October 21, after 142 hours and 30 minutes of searching, authorities called off the operation, assuming all 45 people aboard had perished in the crash.

Building Shelter Amid Death and Debris

On the first night after the crash, five more people died: co-pilot Dante Lagurara, Francisco “Panchito” Abal, Graciela Augusto de Mariani, Felipe Maquirriain, and Julio Martínez-Lamas.

The 27 survivors quickly began clearing wreckage and broken seats to carve out a crude shelter inside the 2.5-by-3-meter fuselage. It was cramped but vital.

They used luggage, seat cushions, and snow to insulate the cabin’s open rear, trying to seal out the brutal cold as they braced for the unknown.

Marcelo Perez: Survival Through Ingenuity and Leadership

As freezing nights dragged on, survivors improvised. “Fito” Strauch melted snow for water using metal seat parts and wine bottles, and even crafted makeshift sunglasses.

They repurposed seat fabric for warmth and used cushion covers as snowshoes. Their survival depended on creative thinking, grit, and the shared will to stay alive.

Marcelo Pérez del Castillo, rugby team captain, stepped up as the group’s leader—organizing efforts, maintaining morale, and helping others face each day in the deadly cold.

No Experience, No Supplies—Just Endurance

By day three, Nando Parrado awoke from a coma, only to find his sister Susana gravely injured. He stayed by her side until she died six days later.

Temperatures dropped as low as -30°C at night. Survivors had no winter gear, almost no medical supplies, and only three pairs of sunglasses to prevent snow blindness.

Most had never seen snow before. Raised near the coast, with no experience at altitude, they faced the harshest terrain imaginable with nothing but sheer human will.

The Survivors Managed to Make a Radio Work, and They Learned Devastating News

Among the wreckage, survivors discovered a small transistor radio wedged between seats. Roy Harley, using his electronics knowledge, rigged an antenna with aircraft wiring.

For days, they huddled around it, hoping for good news. On the eleventh day, the message finally came through—but it wasn’t what they’d prayed for.

They heard the broadcast: the official search had been canceled. No one was looking for them anymore. From that moment on, they knew they were completely on their own.

The Moment They Realized No One Was Coming

When the group gathered around Roy Harley’s radio and heard the search had been called off, tears and prayers filled the crushed fuselage—except from Nando Parrado.

While others sobbed, Parrado looked silently toward the towering mountains to the west. Then Gustavo “Coco” Nicolich climbed out, saw their faces, and understood instantly.

“Good news!” he called out with forced cheer. “They’ve canceled the search.” Shock fell over the group. “Why is that good news?” someone asked. “Because,” Nicolich said, “it means we’ll get out ourselves.”

A Terrible Choice: Turning to Anthropophagy for Survival

The survivors’ food supply was shockingly limited—eight chocolate bars, a can of mussels, jars of jam, dried fruit, candy, a bit of rum, and little else.

They rationed every bite. Nando Parrado once went three days eating just a single chocolate-covered peanut. But even strict rationing couldn’t stretch the food far.

With no plants or animals at 12,000 feet, they grew desperate. After the tenth day, knowing the search was over, they agreed: if one died, the others could eat. And they did.

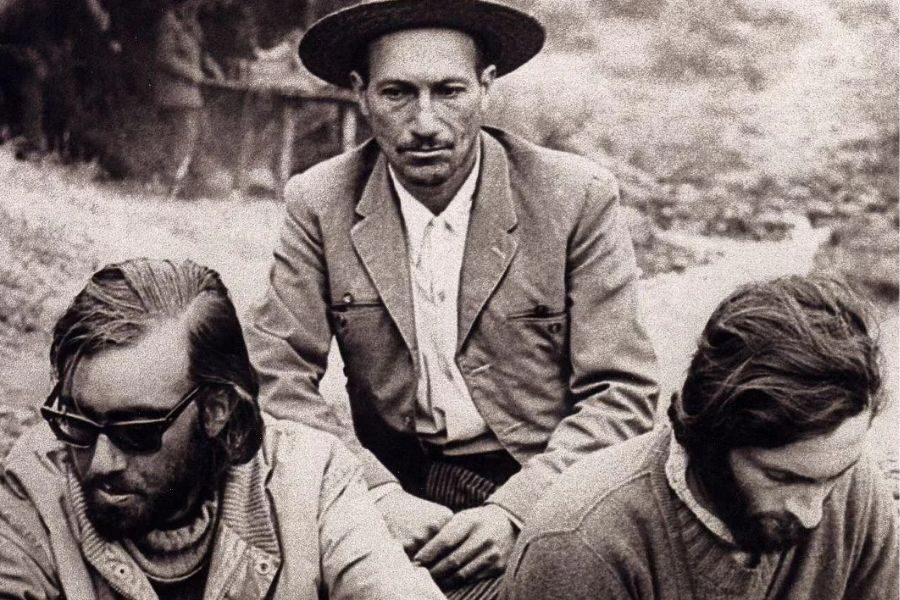

“We Knew the Answer”: Canessa and the Unthinkable Decision

With food gone, the survivors faced a horrifying truth. “Our common goal was survival,” one of the most outspoken survivors, Roberto Canessa, recalled years later, “but what we lacked was food.”

The meager supplies were long gone. “There was no vegetation or animal life. Our own bodies were wasting away just to keep us alive,” Canessa explained.

They knew the answer, but dreaded it. “I went out into the snow and prayed to God for guidance,” he said. He used broken windshield glass to cut flesh, then swallowed the first frozen strip. “Were we savages—or just doing what had to be done?”

Parrado’s Words: “There Was Nothing Left But Ice, Rock, and Flesh”

“In the Andes, the body’s caloric needs are astronomical,” Parrado wrote. They searched endlessly—tearing luggage, checking seat cushions—finding nothing but foam, plastic, ice, and despair.

Parrado guarded his mother and sister’s bodies. Others dried flesh in the sun to preserve it. “There was nothing left,” he said, “except what lay outside.”

They began with skin and muscle. As supplies ran low, some ate hearts, lungs, and brains. “It terrified us,” Parrado admitted, but it was their only chance.

The Avalanche: A Crushing Blow to the Group’s Hope

Seventeen days after the crash, at dawn on October 29, an avalanche slammed into the fuselage, burying it in snow and trapping the survivors inside.

Only one meter of space remained between the packed snow and the roof. Eight people suffocated, including team captain Marcelo Pérez and Liliana Methol, a motherly figure.

The loss of their leader and caregiver was devastating. “It was a terrible blow,” many recalled—another cruel reminder that the mountain would keep testing them, again and again.

New Leaders, False Hopes, and Many Failed Attempts to Escape

After the death of team captain Marcelo Pérez, leadership passed to cousins Eduardo and Fito Strauch and Daniel Fernández, who managed food rations and cut the meat.

Some survivors had already insisted their only hope was to climb west toward Chile, trusting the co-pilot’s final words that Curicó was nearby.

In truth, they were over 55 miles away. Early expeditions failed—altitude sickness, dehydration, snow blindness, and bitter cold made even short journeys nearly impossible in the first weeks.

The Survivors Choose a Team to Search for Help

As the days dragged on, hope shifted toward action. The survivors agreed that someone needed to leave and seek help, no matter how dangerous the journey.

Roberto Canessa, Fernando Parrado, Numa Turcatti, and Antonio Vizintín volunteered. They received larger food rations, warmer clothing, and were excused from daily group duties.

At Canessa’s suggestion, they waited nearly a week for warmer temperatures. Though some doubted their strength, the decision marked a turning point—from waiting to doing.

A Hike Toward Hope Leaded to the Plane’s Missing Tail

The group aimed west, believing Chile was nearby, but a massive mountain blocked their path. They instead turned east, hoping the valley would curve westward.

On November 15, after hiking 1.6 km downhill, they found the plane’s tail section, mostly intact. Inside were clothes, food, rum, cigarettes, medicine—and the aircraft’s radio.

That night, they camped in the tail, lit a fire, and read comic books—momentarily escaping their nightmare. It was a brief pause before the harsh reality returned.

A Desperate Plan, a Frozen Night, and One Final Defeat

After a night nearly frozen to death, the team realized longer treks needed preparation. They returned to the tail with a bold new idea.

Their plan: retrieve the plane’s batteries and use them to power the radio. But each battery weighed 24 kilograms—far too heavy to carry uphill.

Instead, they brought the radio down. Roy Harley tried connecting it, but the voltage was incompatible. After days of failure and a snowstorm, they gave up.

Three More Deaths and a Final Wake-Up Call

On November 15, day 34, Arturo Nogueira died from sepsis. Three days later, Rafael Echavarren followed—both victims of infected wounds and gangrene.

By December 11, day 60, Numa Turcatti died weighing only 25 kilograms. Each death reminded the group: no one would survive much longer without outside help.

Then, a spark of urgency. Through the transistor radio, they heard Uruguay’s Air Force had resumed the search. The message was clear: it was now or never.

With a Homemade Sleeping Bag, Parrado, Canessa, and Vizitín Began Their Final Attempt to Find Help

Realizing they couldn’t survive the freezing nights, the survivors crafted a sleeping bag from insulation, copper wire, and waterproof fabric salvaged from the wreckage.

It was a last-ditch innovation that made escape possible. Without it, climbing through the Andes’ brutal cold would’ve been certain death before help could be found.

On December 12, 1972, Fernando Parrado, Roberto Canessa, and Antonio Vizintín began their final push west—risking everything to find rescue, or die trying.

Ill-Equipped and Misguided: The Climb Began with False Assumptions

The climbers believed they were at 2,100 meters, based on the plane’s altimeter—but in reality, they were at nearly 3,600 meters above sea level.

Convinced they were near Curicó, thanks to the pilot’s final transmission, they packed only three days’ worth of meat—expecting a short trek to safety.

Parrado wore three jeans, three sweaters, and socks in a plastic bag. With no gear, map, or climbing experience, they mistakenly chose the steepest route—straight uphill through waist-deep snow.

After Reaching the Summit, The Two Longtime Friends Realized Their Journey Had Just Begun

On the third morning of the climb, Canessa stayed at camp while Parrado and Vizintín pushed forward, reaching a sheer, 100-meter ice wall.

Determined, Parrado carved steps with a stick and reached the 15,260-foot summit. Expecting green valleys, he instead saw endless snow-covered peaks in every direction.

Stunned, they realized their journey had only just begun. Vizintín returned to camp to conserve food, and Canessa, upon reaching the summit, thought: “We’re dead.”

Choosing a Path and Accepting the Risk of Death

From the summit, Parrado saw two bare peaks to the west with a valley leading toward them. He believed that was their path to freedom.

Canessa agreed to follow. Unknown to him then, an easier rescue route lay east. But trusting instinct, they descended toward what seemed like the only hope.

At the peak, Parrado said, “I’d rather walk to meet my death than wait for it.” Canessa replied, “Now we’re going to die together.” Then they climbed down.

Signs of Life and the First Human Contact

Parrado and Canessa followed the valley they had seen from the summit, eventually reaching the headwaters of the San José River, a tributary of the Portillo.

They followed the river downhill, reaching the snowline. Slowly, hints of humanity appeared—an old campsite, footprints, and on the ninth day, the sight of grazing cows.

That evening, while gathering wood, they spotted three men on horseback across the river. Parrado shouted, but the roaring water drowned his voice. One rider yelled, “¡Tomorrow!” and returned the next day.

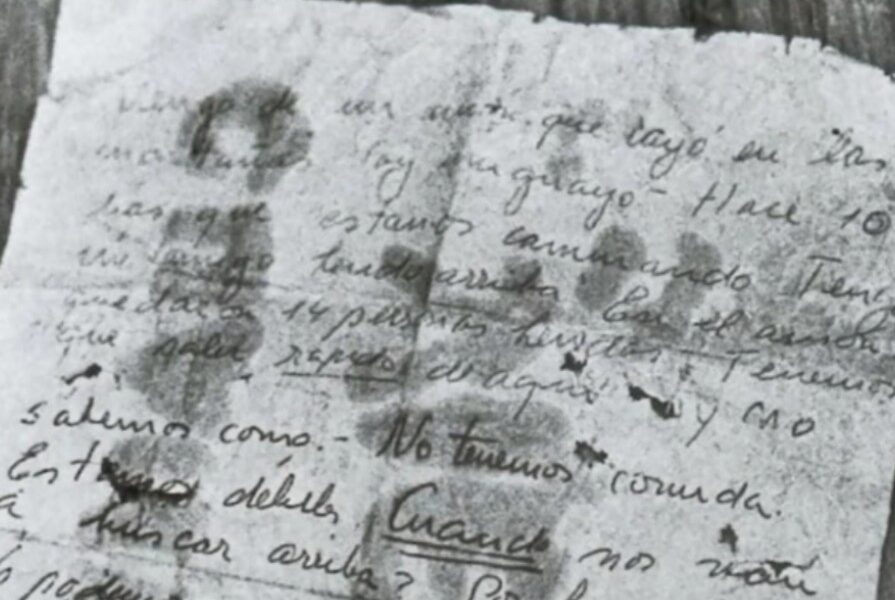

They Wrote a Letter Asking for Rescue

On December 21, 1972, one of the horsemen returned. He wrote a note, tied it to a stone with string, and threw it across the river.

Parrado picked it up and wrote back desperately: “I come from a plane that crashed in the mountains. I’m Uruguayan. We’ve been walking for ten days.”

He added, “My friend is injured. Fourteen others are still at the crash site. We’re weak, starving, and can’t walk anymore. Please—where are we? When will help come?”

A Chilean Muleteer Went Looking For Help After He Goit their Note

Chilean muleteer Sergio Catalán read Parrado’s note and gestured that he understood. He quickly conferred with his two sons, who were riding alongside him.

One son recalled a man—Carlos Páez’s father—had come weeks earlier asking if anyone had heard news of a plane crash in the Andes.

Stunned that anyone could have survived, Catalán tossed bread across the river to the starving men, then rode ten hours west—determined to bring back help.

The News Spreads and the Heroes Rest

After Sergio Catalán delivered the miraculous news, Carabineros from Puente Negro relayed it to the Colchagua Regiment in San Fernando, which contacted the Army in Santiago.

Meanwhile, Parrado and Canessa were taken on horseback to Los Maitenes. There, for the first time in days, they ate, rested, and felt relief.

They had walked nearly 37 miles in 10 days. Canessa, having lost nearly half his body weight, now weighed just 44 kilograms—exhausted, but alive.

When He Knew Help Was on Its Way, Roberto Canessa Buried the Pieces of Human Flesh He Had Carried

Once he knew help was finally on its way, Roberto Canessa took a quiet, personal step—he buried the last pieces of human flesh he had carried.

He knew he wouldn’t need it anymore. The nightmare was ending. Real food, real care, and rescue were no longer just a hope but a reality.

For Canessa, burying that flesh meant leaving behind the unimaginable choices of survival. “We were going back to normal,” he said. “We had made it out.”

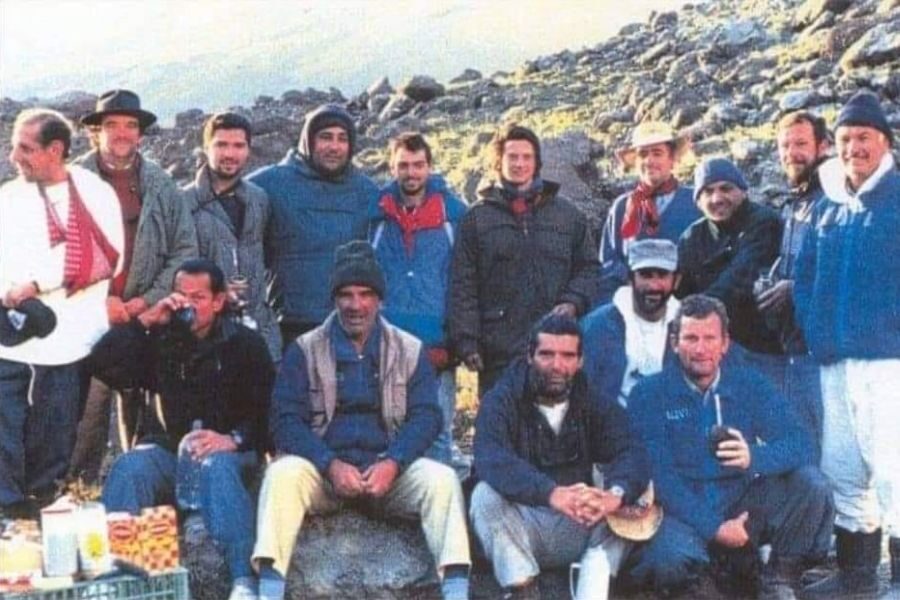

Rescue at Last: The Helicopters Arrive

On the afternoon of Friday, December 22, two helicopters finally reached the survivors. The steep terrain allowed only one landing skid to touch the snow.

Because of the altitude, only half of the group could be rescued on the first trip. Four brave rescuers chose to stay overnight with those left behind.

At dawn on Saturday, December 23, the helicopters returned. The last survivors were flown to hospitals in Santiago, treated for frostbite, dehydration, broken bones, and unimaginable exhaustion. After 72 days, they were finally safe.

A Return to Life: Hospitals, Families, and Headlines

After the final rescue on December 23, 1972, the survivors were flown to hospitals in Santiago—most taken to the Hospital de la Fuerza Aérea de Chile.

There, they were treated for malnutrition, frostbite, altitude sickness, and broken bones. Soon after, they were reunited with their families—emotional scenes of joy and disbelief.

News of their survival spread like wildfire. Journalists from around the world rushed to Chile. No one could believe it—after 72 days in the Andes, they were alive.

After the Rescue: Joy, Grief, and a Harsh Spotlight

The days following the rescue were filled with overwhelming emotion. Families of the survivors celebrated, while others mourned those who hadn’t made it home.

When it was revealed in a press conference that they had survived by eating the bodies of the dead, public opinion shifted.

Many reacted with judgment and disbelief, unable to understand the impossible choices made at 12,000 feet. However, over time, public judgment slowly gave way to empathy.

A Final Resting Place in the Mountains

It was decided that those who died in the Andes would be buried near the crash site, in a common grave carved into the snowy mountainside.

The survivors and families agreed—it was fitting that they rest where they had endured so much, surrounded by the peaks that witnessed their final moments.

Over the years, loved ones, survivors, and strangers have visited the site. It remains a place of remembrance, reflection, and deep respect for those who never came home.

From Tragedy to Legacy: The Story That Inspired the World

The incredible survival of the Andes plane crash didn’t just make headlines—it inspired a wave of books, films, and fictional works around the world.

Survivors like Nando Parrado (Miracle in the Andes) and Roberto Canessa (I Had to Survive) shared their powerful accounts, offering firsthand reflections on courage and trauma.

The story also inspired the best-selling book Alive by Piers Paul Read and several films, including Alive (1993) and Society of the Snow (2023), captivating audiences globally with its raw humanity.

A Legacy of Resilience That Lives On

Of the 16 survivors, two—Javier Methol and Álvaro Mangino—have since passed away. Their absence is felt deeply by those who remain.

The 14 remaining survivors continue to reunite every year—brothers not by blood, but by something stronger. Their gatherings are filled with emotion, reflection, and quiet gratitude for life.

Their story is a living testament to resilience, love, and human connection. Decades later, they remind us that even in the darkest moments, hope must never be abandoned.